The power of the post-it: on studying, sensemaking and stationery

Last week I tweeted about my joy at being back in reading mode and, as a consequence, having an excuse to indulge in stationery.

I have a study kit again (highlighers, post-its, notebook/research diary) … It feel SO DAMN GOOD. #lovestationery — Emma Coonan (@LibGoddess) October 10, 2014

I was entertained that my tweet got favourited, suggesting that I’m not alone in seeing study and stationery as mutually fulfilling partners. I also got a request for a peek at my research diary, which I’m very happy to comply with because it reminded me how much I love seeing how other people lay out their “vehicle for ordered creativity” (Schatzman & Strauss, 1973). What I mean by ‘research diary’ is not the neatly-written lab report designed to be shared and perhaps assessed, but the scruffy, tatty notebook we carry around and scribble in privately. In my kind of research diary we don’t write for anyone else’s eyes. It’s a force of nature, a place where our thoughts rampage unfiltered by academic proprieties. And it’s really not very tidy – because as I may have said a few times before, the process of knowledge creation is by its nature a messy affair.

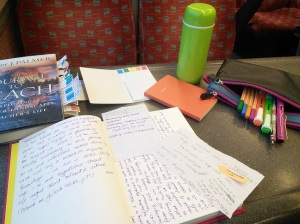

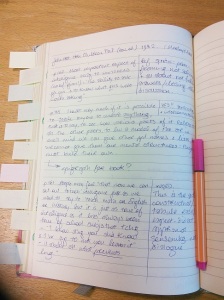

Above is my newly-started research diary along with the odds and sods that make up my study kit – pens and highlighters of various colours, post-its of various sizes, and a nifty little book of tear-out pages that acts as my mobile To Do list. I find that there’s always a degree of self-consciousness about plunging into a new notebook, a desire to make the inside as neat and pretty as the outside. But only two pages in to this new one, the mess and the overflow have already started! That torn scrap with the orange post-it stuck on it is a bit of thinking from another time and place that needs to sit alongside what I’m doing now. It will float around in this perilous, unanchored state for who knows how long, until I find the right place in the new diary to glue or staple it in (which of course, along with all the other similar thought scraps, will end up contorting and bending the outside so it does, in effect, match the inside – just not in any way that could be called ‘neat’).

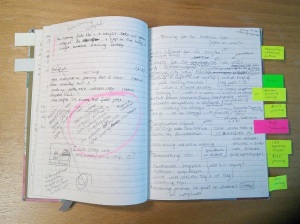

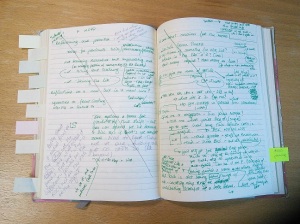

Here’s my previous notebook. It’s less of a ‘pure’ research diary and even more of a mongrel planning-thinking-writing tool, as alongside research notes it contains lesson planning for work, bits of writing towards articles and a book, and random thoughts inspired by the Fen landscapes. In fact it’s such a patchwork of various facets of my life that I went back through it and post-it’d it so I could find my way around all the bits that are still ‘live’.

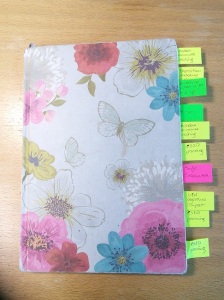

Post-its are also my go-to notemaking strategy when I’m in a flailing-round-trying-to-orientate-myself phase such as starting a research project, or entering a new field (as I am at the moment). Orientating yourself in a new field often demands that you read classic monographs and textbooks rather than articles and papers, which means that you have no hope of buying, printing or copying everything you need – which in turn means you can’t interact with or answer back to the text by annotating it directly. For me this is a real problem. (Please don’t be shocked: of course I write in my books. Books are knowledge tools, not decorative artefacts. As I A Richards said in 1924, “A book is a machine to think with”.)

When you can’t write in books because they’re not yours, but you’re not yet at the stage where you can mash up what a writer is saying with other stuff you’ve read and with your own thoughts – which is what the research diary is for – I find the post-it strategy is perfect. Although it’s not in the same league of bibliographic criminality as marginal annotations, I know some libraries aren’t crazy about people putting (even slightly) sticky things (even temporarily) in their books. However, I’m resigned by now to the fact that I’m a bad librarian … and active reading is fundamentally necessary in order to locate yourself in your field, to find a standpoint, and to join the dialogue. Being able to ‘talk back’ to the literature is the foundation stone of a contribution to knowledge.

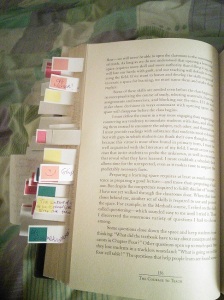

Here’s another form of answering back (and another page from my old diary): the ‘double entry notemaking’ idea, where every time you copy or paraphrase something from the original, you also write your reason for grabbing that quote or idea, your response to it, or both. I love the emphasis this places on the reader’s context and reasons for reading. In practical terms it’s a great way of futureproofing the work that goes into reading and notemaking, but it goes further than that: as you capture your response to the text you start developing your own thoughts and making connections between concepts. And when there’s this much stuff chasing chaotically around in your mind, keeping hold of those connections needs all the help it can get!

Lest anyone think I might be pushing the connection between studying and stationery a bit far, it’s worth bearing in mind that according to constructivist thinking, learning takes place through individual sensemaking: through perceiving and building patterns, relationships and hierarchies for yourself rather than assimilating someone else’s conceptual model. John Holt says this beautifully and resonantly:

I doubt very much if it is possible to teach anyone to understand anything, that is to say, to see how various parts of it relate to all the other parts, to have a model of the structure in one’s mind. We can give other people names, and lists, but we cannot give them our mental structures; they must build their own. (1982, 145).

(This is one of the quotations on the double-entry notemaking page, above. My response is pretty concise: it says “YES!!” in large letters : ) ) If we accept the constructivist approach to learning, it follows naturally that how we organise our knowledge influences both how we learn and how we apply what we know (Ambrose et al., 2010). I think this is one of the most important principles of both learning and research, and yet we rarely talk about it explicitly or devote much time to reflecting on the practices we use to organise and make sense of knowledge, and how they interact with the practices of our academic discipline as well as our own desire or need to learn. When I do get to talk about how we organise knowledge, usually in my information skills classes, I always come away feeling inspired. Our tools for recording, ordering and juxtaposing knowledge scraps are hugely various and reflect our individual, unique approaches to learning. They can be analogue or digital, can range from the hi-tech to the humble. But perhaps what I find most endearing is that even the unassuming post-it can play a part in making connections and, ultimately, making a contribution to the dialogue.

Addendum

Researchers (and anyone else) feeling the #stationerylove, please do look at these other lovely posts on creative uses of notebooks and stationery:

My notebooks and other animals by @samanthahalf, which shows some notebooks that are even more beautiful inside than out;

@florilegia‘s post on keeping a ‘commonplace book’, An anthology of one’s own;

Stationery love (hurrah!) by @Aurelie_Sol, which has some wonderful tips on journalling and notebooks as organisational tools for your thinking.

This post got some awesome replies on Twitter, ranging from other people’s beautiful notebooks (and their contents) to a great conversation with @donnarosemary about approaching a new research field. There’s a Storify of responses at https://storify.com/LibGoddess/approaching-reading-in-a-new-field.

It’s a fabulous post: I have really enjoyed reading it, and am coming back for a second look!